6 Upper Merrion Street

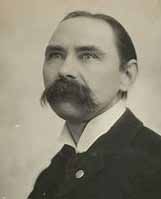

One of the most decorated soldiers in history was born in 6 Upper Merrion Street, Dublin in 1769 (now the Merrion Hotel). The son of a noble, but impoverished family, Arthur Wesley (later changed to Wellesley by his eldest brother who became Governor General of India) did not show much flair for anything other than playing the violin when he joined the army as an ensign in 1787, having been withdrawn from Eton due to a downturn in the family’s finances.

He sat in the Irish House of Commons as member for Trim, Co. Meath. After his proposal of marriage to Kitty Pakenham had been turned down he applied himself to military life with a determination of purpose that was to be his trademark and strength. After his first taste of action in Holland he was left with a distinctly low impression of many of his commanding officers, an experience that only increased his awareness of the value of preparation and attention to detail. Suitably prepared, he used his skill to good effect while in India, after which he had become a rich man and had been promoted to major-general.

Back in England he renewed his relationship with Kitty and eventually, not having seen her for ten years, married her in what he later described as the ‘biggest mistake of his life’. Difficult though the marriage was, he craved and immersed himself in the security and familiarity of the army. This is where he was at his best and within a short time he was back in action – this time against the armies of Napoleon (who coincidently was also born in 1769).

He led the British Army that fought against the French in Spain and Portugal during the Peninsular Wars. His scorched earth policy, allied to superb defensive positioning, allowed the opposing army little freedom of movement and significantly reduced its ability to feed itself and inhibit its fighting capability. This led to the French being expelled and Wellesley occupying Toulouse in 1814, whereupon he was promoted to field-marshal and made Duke of Wellington. He was subsequently appointed as Ambassador to Paris, from where he travelled to negotiate the Congress of Vienna 1814-15.

While in Vienna he learned of Napoleon’s escape from his island prison on Elba, and the subsequent gathering of his once proud army in France. Wellington was put in charge of the British and Dutch forces that left Brussels for Waterloo (8 miles to the south). June 18th 1815 has gone down as one of the most momentous days in European history, when late in the day, Wellington, who was facing Napoleon for the first time on the battlefield, survived enormous early attacks and won the day with the late and critical arrival of Marshal Gebhard Blucher’s Prussian army. Irishmen fought that day on both sides with 10,000 in the British ranks alone, and it is reckoned that almost 50,000 men were killed or injured in the bloody battle. It was a crushing blow for Napoleon who resigned as emperor four days later. His transportation to the remote island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic brought French expansionism to an end, and allowed Britain to ‘rule the waves’ and gain a position of pre-eminence in trade and influence.

A political career beckoned and Wellington became a minister in 1819 and Prime Minister in 1828. It was during his time in Downing Street that Catholic Emancipation was granted (1829). Various offices, such as the Chancellor of Oxford University and Commander-in Chief of British forces, were bestowed upon him. Apart from these he was also made a prince in Holland, a duke in Spain and a marshal in seven European armies. Parliament, in recognition of his service, granted him funds to build a home, Apsley House, which later became known as ‘No. 1 London’. In late life he led a simple and austere existence in his castle in Walmer, Kent where he died in September 1852. His wish to be buried nearby was ignored, and he was finally laid to rest with all the pomp and circumstance that could be mustered in St. Paul’s Cathedral.

‘Waterloo’ relief on Wellington Monument

The good people of Ireland (in fact, he denied his Irishness by proclaiming ‘that not everyone born in a barn was a horse’) had already showed their respect by raising over £20,000 for the erection of the Wellington Monument, designed by Sir Robert Smirke. The Lord Lieutenant, Lord Whitworth, laid the foundation stone on the site of the Salute Battery, in the Phoenix Park, in June 1817. Unfortunately the funds dried up and the obelisk was finished but nearly fifteen feet short of the desired height. The reliefs around the base of the monument, which tell of his military victories and political reforms, were cast from captured cannon guns, appropriate indeed when they recount the heroic life of one who is known to history as ‘The Iron Duke’.

Wellington Monument in the Phoenix Park, Dublin