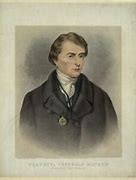

Edith Maud Gonne McBride (1866–1953), the political activist was born on 21 December 1866 at Tongham Manor, Farnham, Surrey and was the eldest daughter of three daughters born to Capt. Thomas Gonne and Edith Cook. Gonne’s family were wealthy importer of Portuguese wines and the Edit Cook came from a family of successful and respected drapers in London. Edit, who suffered from tuberculosis, sadly died in London after giving birth to her third daughter. The infant, Margaretta, died soon afterwards.

In 1876 then Maj. Gonne was appointed military attaché to the Austrian court, and the family spent time in the south of France. Maud liked being in France as much as being in Ireland or England, and spoke French fluently. In 1882 Gonne, after a stint in India, was posted to Dublin as assistant adjutant-general at Dublin castle. Maud said that she watched the arrival of the new lord lieutenant from a window in the Kildare Street Club on the 6th May 1882, the same day that the Phoenix Park murders took place.

By 1886 Maud Gonne’s political thinking was shifting to that of a nationalist, after she and her father witnessed the horror of the evictions in the country. She said that he was going to resign from the army and stand as a home rule candidate. This, however, never happened as Gonne died from typhoid fever on the 30 November 1886.

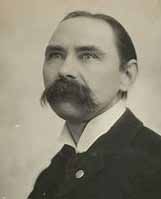

She met WB Yeats in Dublin 30 January 1889 and he was immediately besotted with her beauty: tall, bronze-eyed, and with a ‘complexion . . . luminous, like that of apple-blossom through which the light falls’. He fell in love with her, and wrote many poems about her. She played the lead role in his play Cathleen ni Houlihan, and although he proposed to her twice she refused his offers.

She died at Roebuck House, Clonskeagh, Dublin on 27 April 1953 and was buried in Glasnevin cemetery two days later.