There are many bridges over the Liffey and the site of what is believed to have been the first one – Ford of the Hurdles – is where the Father Matthew Bridge now stands. After the Norsemen arrived along the river and fought with the locals, a bridge was built on a shallow ford that lasted until the 11th century. It was probably built of wood, ropes and stones and no doubt would have been repaired after flood damage. King John had a new bridge built in its place in 1214 and this lasted until it was washed away in the 1380s.

No replacement was built until the local Dominicans friars had a stone bridge erected in 1428, and this was known as Bridge of Dublin, and later as the Old Bridge. This bigger bridge had four arches, and towers at either end. There were numerous shops and housing on it, and there was also a chapel (still in use in 1762), an inn and a bakery. And as it was the only crossing point on the river all pedestrian, livestock and horse-drawn traffic used it.

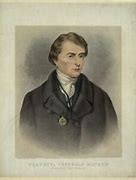

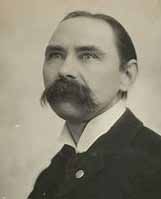

After almost four centuries use the northern end of the bridge collapsed and it was decided to replace it, and the version that we see and use today was completed in 1818. This new bridge was called the Whitworth Bridge in honour of the then Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Charles Whitworth. This addition to the Liffey history is a masonry arch bridge which is 145 ft (44 m) long, with three elliptical arches. It was built for the Port of Dublin between 1816-1818 and was designed by George Knowles and James Savage, who had teamed-up for the nearby O’Donovan Rossa Bridge the previous year, and cost £26,000. . It was renamed as Dublin Bridge in 1922 before being retitled the Father Matthew Bridge in 1938, in honour of the founder of the Irish Total Abstinence Society who was inspired to save ‘one poor soul from intemperance and destruction’.