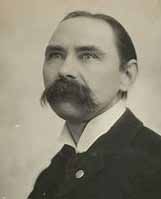

Sir John Lavery

Lavery was born in Belfast on 20th March 1856. His father was an unsuccessful publican who was drowned when his son was only three years old; and not too long afterwards he also lost his mother. Orphaned at such an early age he was raised on a farm north of the city by an uncle, until he was ten years old when he travelled to Scotland where he was cared for by other relatives.

He went to the Haldane Academy in Glasgow and was later apprenticed to a photographer/painter where his love of art was fired. From this time on it was his singular ambition to become a painter and he studied at the Glasgow School of Art. By the time he was twenty-three he had set-up as an independent artist. In 1879, in order to improve his technique and find out what was going on in the art world, he went to London where he studied at Heatherley’s School of Art for six months.

Hungry for knowledge he travelled to Paris in 1881, where he studied drawing and fine art at the Academie Julian. In 1883, he visited the artists’ colony of Grez-sur-Loing (which is about 70km south of Paris) and got to know the Irish artist Frank O’Meara, who was from Carlow, and the French painter Jules Bastien-Lepage, both of whom influenced his painting style. Among the many artists that he met there were the American painter John Singer Sergeant, writers Robert Louis Stevenson and August Strindberg and the English composer Frederick Delius.

The Bridge at Grez

While at the artists’ colony he became absorbed with landscape painting in the open air (en plein-air), which was very much in fashion due to the influence and growing interest in Impressionism. It was the ‘in thing’ and Lavery wanted to know all about it. His painting The Bridge at Grez (sold by Christie’s in 1998 for £1.3m) clearly shows how he had taken on board the influences that surrounded him. Later in the year he exhibited his first French landscape, Les Deux Pecheurs.

Barry Edward O’Meara

O’Meara’s grandfather, Barry Edward O’Meara, was a surgeon in the Royal Navy and sailed on board the HMS Northumberland with Napoleon Bonaparte, as his physician on St Helena. Later he wrote about his experience in Napoleon in Exile, or A Voice From St. Helena (1822). Among the mementoes that O’Meara brought back from St Helena is Napoleon’s toothbrush with N stamped on its silver handle. He gave it to O’Meara, and years later it made its way to the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland on Kildare Street.

In 1885 Lavery he returned to Scotland and became one of the leading lights in the Glasgow Boys group of painters that included, among others, James Guthrie, James Paterson, and David Gauld. These painters were at the forefront of introducing modern art into Scotland, and many often painted outdoors, preferring the immediacy of the light and atmosphere to the sterility of the studio. The following year brought him his first significant recognition when his painting The Tennis Party (1885) was shown at the Royal Academy, London where it was widely admired and later purchased by the great German gallery Neue Pinakothek in Munich.

In 1888 he won the commission to paint Queen Victoria’s State Visit to the Glasgow International Exhibition. He was subsequently granted a sitting by the Queen and from then on his position as a much sought-after painter was assured. After that he could afford to move to London where he set-up his studio in Cromwell Road, Kensington. His portraits of the rich and famous made him a wealthy and busy man, and one who liked to travel. This lust for new places took him across Europe where his works featured in exhibitions in Paris, Berlin and Rome. His paintings were popular on the Continent, so much so that two of them, Father & Daughter and Spring, were acquired by the Louvre. Also, he was given the rare honour of having a one-man show at the Venice Biennale of 1910. And for a time he had a studio in Tangiers where he liked to paint outdoors in the brilliant light.

Lady Lavery

Lavery was first married to Kathleen MacDermott in 1889, but she tragically died of tuberculosis in 1891 after the birth of their daughter Eileen (later Lady Sempill 1890-1935). In 1904, while on holidays in Brittany, Lavery first met Hazel Martyn who was then engaged to a Canadian doctor, Edward Trudeau, who died five months after their marriage. Lavery met Hazel again, and in 1909 he married the beautiful Irish-American who was almost thirty years his junior. They had a step-daughter, Alice Trudeau. During the First World War he, like William Orpen (from Stillorgan, Dublin) was appointed as a war artist by the British Government and he was knighted in 1918, with Hazel becoming Lady Lavery.

Irish Delegation

They lived at 5 Cromwell Place, South Kensington, a palatial residence where they entertained the great-and-the-good of British society, with Winston Churchill, Hilaire Belloc, George Bernard Shaw, Lytton Strachey and WB Yeats being regular guests. With her undoubted beauty and poise Hazel was known as the foremost hostess in London. During the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty negotiations the Laverys lent their home to the Irish delegation who they often met. To this day there are rumours of an affair between Hazel and Michael Collins but these remain unproven.

Due to his assistance and hospitality during the Anglo-Irish Treaty negotiations the Irish Free State, in 1928, commissioned Lavery to design the artwork for the new banknotes. He painted Hazel as Caithlin ni Houlihan, the female personification of Ireland, and her image was on all notes issued until 1977.

Hazel, Lady Lavery ‘On the money’

Lavery eventually returned to Ireland and lived in Rossenarra House, Kilmoganny, Co. Kilkenny where he died on 10 January 1941, aged 84. He was later interred in Putney Vale Cemetery, London where Hazel had been buried six years earlier.

Rossenarra House